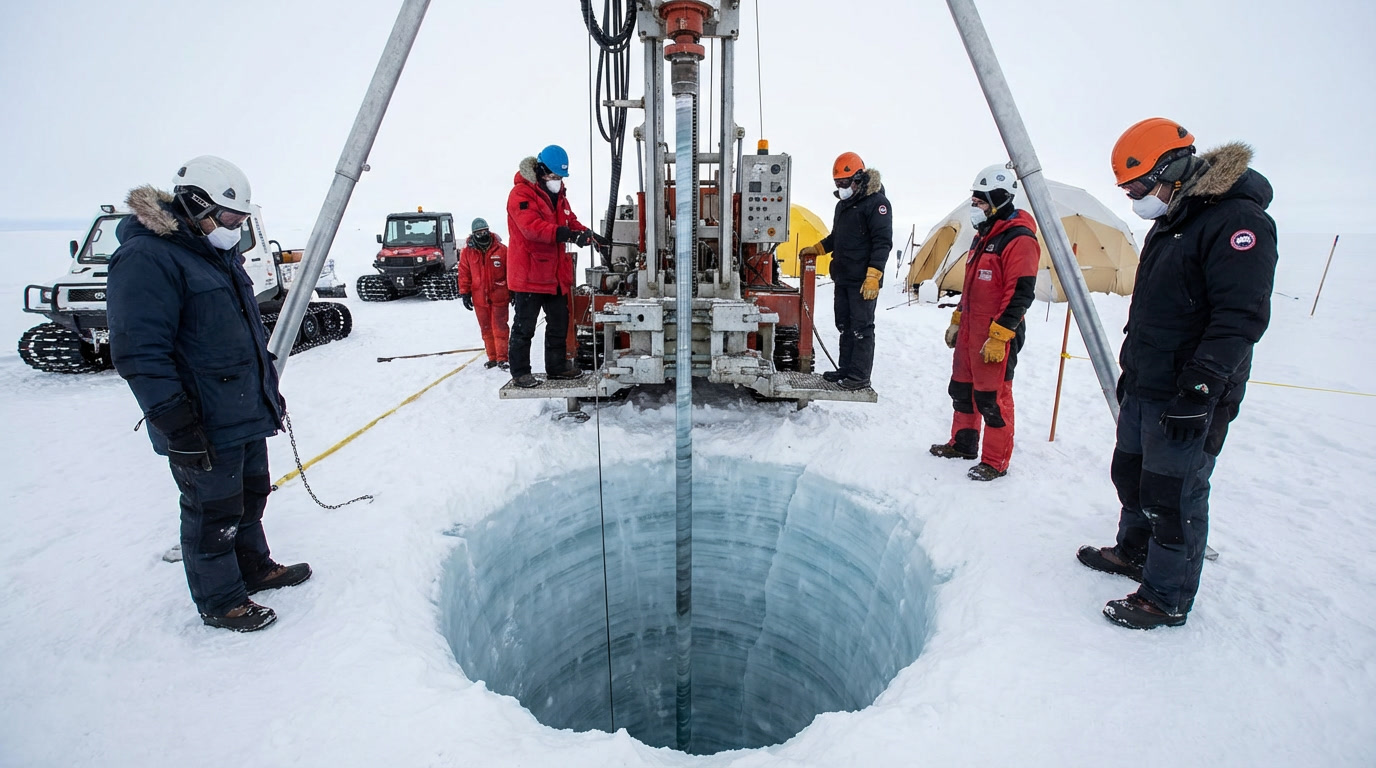

The drill shuddered like a trapped animal, then went quiet. On the frozen surface of Antarctica, a small group of scientists leaned over a steel-rimmed hole that dropped more than two kilometers straight down through ancient ice. Their breath hung in the air, mixing with diesel fumes and the low whistle of wind sweeping across the plateau. One researcher glanced at a monitor and broke into a grin that felt wildly out of place in one of the coldest environments on Earth.

Deep below their boots, a metal cylinder had just punched through to something no human had ever touched before: mud and rock sealed away since long before mammoths, long before humans, long before Antarctica became the white continent we know today.

What came back up looked like sludge.

It was anything but.

A Lost Landscape Beneath Two Kilometers of Ice

When the first sediment cores emerged, there was no dramatic reveal. No sparkling crystals. No alien shapes. Just brown, waterlogged cylinders that wouldn’t look out of place on a riverbank.

Read Also- Emergency declared in Greenland as researchers spot orcas breaching near melting ice shelves

Inside a heated lab container, exhausted scientists began the slow ritual of slicing, labeling, photographing. Weeks of cold, noise, and broken sleep had trained them not to expect miracles.

Then the microscope told a different story.

The sediment wasn’t dead. It was crowded with clues: fossil pollen grains, plant wax residues, mineral fragments smoothed by flowing water. Shapes carved not by crushing ice, but by rivers. By rain. By roots.

The samples came from beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet near Dome C, where ice above reaches roughly 2.7 kilometers thick. This region has long been considered one of the most stable, permanently frozen places on the planet. For decades, scientific consensus held that it had remained buried under ice for at least 34 million years.

The mud disagreed.

Chemical signatures embedded in the sediment pointed to a world that once breathed. A cool, temperate landscape with vegetation. Shrubs. Mosses. Possibly small trees clinging to rocky slopes. Not a jungle, but unmistakably alive.

Dating methods kept converging on the same moment in deep time: about 34 million years ago, when Earth shifted from a warm “greenhouse” world into the colder “icehouse” climate we still inhabit today.

Under what is now endless white, there were once valleys shaped by rivers and hills that rustled in the wind.

How Scientists Drill Into the Past Without Destroying It

Reaching that hidden world isn’t anything like drilling for oil.

Antarctic ice is a fragile archive. Each layer traps ancient air bubbles, dust from long-gone deserts, ash from extinct volcanoes. One mistake can contaminate millions of years of history.

To get through more than two kilometers of ice intact, teams rely on ultra-clean hot-water drilling systems or specialized mechanical drills. They melt or cut a narrow shaft downward, then lower a separate coring tool designed to gently collect sediment from the bedrock below.

The process takes months. Often under constant daylight. In temperatures cold enough to drain batteries and crack metal.

One of the team’s biggest fears was simple: what if there was nothing there?

What if, after all the logistics, funding, and risk, the drill hit sterile rock dust?

Then came the moment when a single pollen grain—carried by wind or river tens of millions of years ago—appeared under a microscope. A tiny fossil that should not exist beneath kilometers of ice.

From there, the detective work intensified.

Sediment layers were scanned with CT imaging. Fossils were teased out with needles thinner than eyelashes. Isotope ratios of oxygen and carbon were compared with marine records from around the globe.

As one scientist involved in similar work put it, “Each grain in that mud is a piece of a landscape we can’t walk on anymore. We’re rebuilding a world from crumbs.”

Why This Ancient Mud Matters Now

This discovery isn’t just about rewriting textbooks.

The buried Antarctic landscape captures the moment Earth’s climate flipped. Around 34 million years ago, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels dropped, oceans cooled, and ice sheets began spreading across Antarctica. The sediment beneath today’s ice preserves the before-and-after snapshot.

Here’s where things get uncomfortable.

Today, CO₂ levels are racing back toward those ancient values. During the period recorded in the mud, Antarctica did not have a continent-wide ice sheet. It had rivers, vegetation, and exposed ground.

That doesn’t mean Antarctica will turn green anytime soon. Ice sheets respond slowly, over thousands of years. But it does mean they are not permanent. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet has vanished before, and climate models suggest it could retreat again if warming continues long enough.

According to NASA climate data (https://climate.nasa.gov) and assessments from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (https://www.ipcc.ch), ice loss in Antarctica plays a major role in long-term sea-level rise and global ocean circulation.

The decisions made this century won’t just affect coastlines in our lifetimes. They may set processes in motion that unfold for millennia.

The Human Scale of a Geological Shock

There’s a strange emotional weight in learning that the coldest place on Earth was once alive.

We think in decades. Ice thinks in epochs. Politicians think in election cycles. Ice sheets respond to physics, not opinion.

One researcher summed it up quietly after a long day in the lab: “We’re not discovering an alien planet. We’re discovering versions of Earth we didn’t know existed.”

That sentence carries a heavy implication. Earth has more than one stable personality. Warm Earth. Ice Earth. Flooded-coastline Earth. Forested-Antarctica Earth.

Our civilization has only ever known one.

What This Discovery Asks of Us

The mud beneath Antarctica is like a time capsule no one meant to open. Lifted through a shaft of ice, boxed, flown across the world, and analyzed under fluorescent lights powered by the fossil-fuel age.

It doesn’t scream catastrophe. It whispers perspective.

It asks a quiet, stubborn question: if Earth has flipped climate states before, what story are we writing now—into landscapes we’ll never see?

Future scientists may one day drill through what remains of today’s ice and find traces of our era. Soot. Plastics. Chemical fingerprints. Evidence of a moment when humans had a choice.

The discovery under Antarctica isn’t just about the past.

It’s about what we leave behind.

FAQs:

What exactly did scientists find under the Antarctic ice?

Sediment and rock containing fossil pollen, plant waxes, and river-shaped grains, indicating an ancient landscape with flowing water and vegetation.

How do scientists know it’s about 34 million years old?

They used radioactive mineral dating, fossil analysis, and comparisons with global marine sediment records tied to the onset of Antarctic glaciation.

Does this mean Antarctica was once warm and green?

Yes. At several points in deep time, including around 34 million years ago, parts of Antarctica supported vegetation and running water.